The business world is becoming more connected and interconnected – organisations increasingly rely on services that are supplied or run by other parties, including hardware, software and entire services / capabilities; and these may be geographically dispersed on a global scale. At the same time, supply chains are also becoming increasingly complex, both in breadth – the number of services being outsourced – and depth. Elements of the outsourced services (or entire services) will in turn be sub-contracted to other parties.

Security assurance effort has traditionally focussed on the “end service” and the security of information within it, but this overlooks the fact that:

- Services and capabilities are increasingly distributed, and critical elements of an end service are often delivered by suppliers.

- Sensitive information is disseminated through the supply chain as part of component service delivery and procurement activities.

This means that the way in which risk is managed within the supply chain is poorly understood.

Organisations do not have a good understanding of how the supply chain manages the delivery of critical services and sensitive information, and therefore risks associated with critical business services are not understood by risk owners and cannot be managed. Assurance efforts are likely not delivering a true risk landscape and this leads to decisions being made based on incomplete or worse, misleading information.

Furthermore, risk activities are often conducted at a point in time, but not updated to reflect changes. For example a key sub-contractor may have migrated their services to a non-UK based Cloud Service Provider, leading to sensitive information being held outside the UK. Where security controls are specified in contracts with suppliers, these are rarely monitored through life.

Organisations need to understand the risks associated with their supply chain, both in terms of the delivery of business-critical services, and security of sensitive information or information relating to critical service delivery.

To achieve this requires a good understanding of:

- a. How end-services are delivered and crucially which aspects are critical

- b. Who is responsible for critical service delivery and how that supply chain is structured

- c. How the supply chain applies security controls and whether these controls are appropriate and well managed

- d. What information is linked with the end-service and how that is distributed and managed within the supply chain

- e. How the end-service would be impacted if a supply chain element were disrupted in some way through a cyber incident

Fundamentally, when elements of a service are outsourced, the level of risk accepted should not automatically increase. It is not possible to outsource entirely the risk associated with a service. Therefore, risk owners need assurance that appropriate controls are in place throughout the supply chain, and to understand the level of risk incurred in current and future supply chain engagements.

Supply chain is recognised as a key link in the chain of cyber security and cyber resilience. The UK Government Cyber Security Strategy 2022-2030 has security of supply chain as a key outcome, for example. Despite this, according to the 2023 Cyber Security Breaches Survey, only “13% of businesses review the risks posed by their immediate suppliers”. Gartner’s 7 Top Trends in Cybersecurity (published in April 2022), predicted that by 2025, 45% of organisations worldwide will have experienced attacks on their software supply chains, a three-fold increase from 2021.

Connected versus Isolated Systems

There is a distinct difference in the threat level from supply chain when considering systems that are isolated from external untrusted networks (i.e. the Internet) and those which are externally facing. For those isolated systems, supply chain may present the most viable cyber exposures, whether that is the provision of patches / updates, service support or replacement hardware.

Supply chain-based activity by an adversary can occur throughout the Cyber Kill Chain. In general, there are two factors which influence the level of threat associated with the supply chain:

Targeted vs Non-Targeted:

- Non-targeted attacks are those where an adversary has created an exploit and an organisation is affected by this despite not being the end target. The Solarwinds vulnerability is an example of where an attack likely developed for a specific purpose impacts a much larger number of organisations globally.

- Targeted attacks: an adversary develops an attack specific to a service.

Disruptive vs Intelligence gathering – the aim of the adversary varies depending on the stage in the Cyber Kill Chain:

- Intelligence Gathering: In early stages, the aim may be to gather information to develop or execute an attack. For example, if the adversary can identify that a supplier delivers a critical service, and that there is no resilience, this information can be used to deliver an impact. Alternatively, if the adversary can identify that a service uses certain software, it allows more targeted phishing and associated malware to be developed.

- Disruptive Attacks: In later stages, the attack may be disruptive, either on the supply chain itself or on the end capability via the supply chain.

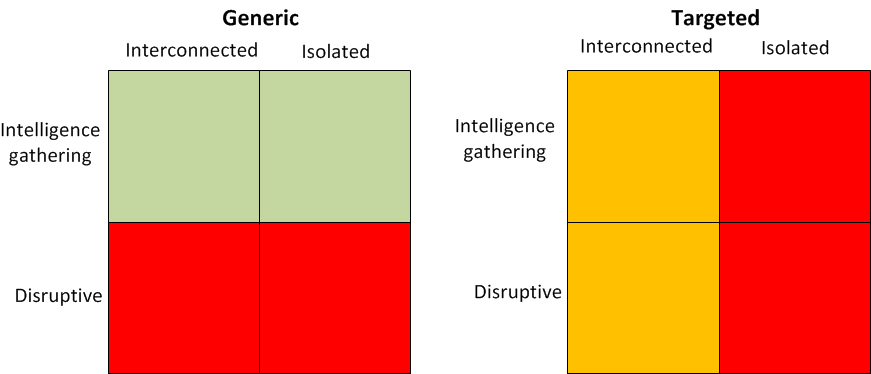

The diagram below provides an overview of the cyber threat associated with the supply chain:

For generic attacks, the threat associated with intelligence gathering is low as this is not the aim of the adversary. However, the threat associated with disruptive attacks is high due to the reliance on third parties for provision of commonly used components. For targeted attacks, the threat is higher for isolated systems as the supply chain may be one of the only available cyber exposures.

The NCSC provides a series of 12 principles designed to help organisations establish effective security within supply chains. Ultimately, adopting a holistic and risk-based approach ensures that the supply chain is fully understood so that assurance effort can be appropriate to the level of risk, and that appropriate controls can be specified in contracts.

One of the key challenges in assuring supply chains is understanding it. In particular for complex programmes and large organisations, supply chains can be many layers deep and mapping this out and understanding where to focus security effort, is the key first step.

Supply chains can provide or hold one or more of the following:

- Critical Services / Capabilities: services which, if disrupted, would have a detrimental impact. This is assessed on a scale that fits the organisation.

- Critical Identifiable Information: information which is not in itself sensitive, but which identifies that a particular supplier is providing a service that is critical. This is a binary criteria – the information either does identify a critical service, or it doesn’t.

- Sensitive Information: information which if compromised, would have a detrimental impact on the organisation. This is assessed on a scale that fits the organisation.

Leonardo’s approach traces Critical Services, Sensitive Information and Critical Identifiable Information through the supply chain to the point where there is nothing sensitive, to provide an understanding of how services are delivered. At each stage, the level of assurance is assessed to provide an understanding of the associated supply chain risk.

As businesses become increasingly reliant on supply chain for delivery of critical services, the supply chain threat increases and cannot be ignored. It is crucial that the risks associated with supply chain are understood and that risk owners are able to make informed decisions.

A holistic approach to supply chain assurance models the way that supply chain delivers critical services, and holds critical service information and sensitive information; and provides an assessment of the level of assurance at each point. This provides an in-depth understanding of how critical services and information are handled, the security controls in place, and the level of associated risk.