For any aircraft operating in a military theatre, or close to areas of instability, there is a risk that it could be targeted either on the ground or in the air. In the military domain, enemy forces are seeking to degrade the capability of friendly forces and reduce their “freedom of action” and ability to manoeuvre over the battlespace, while in the civil aviation domain, non-state actor groups could target passenger aircraft as part of a wider terror or insurgency campaign.

In either scenario, the primary threat for low-flying aircraft is from a man-portable air defence system (MANPADS). MANPADS come in various sizes and configurations but are traditionally a shoulder-fired surface-to-air missile (SAM) comprising a missile tube, launching mechanism and battery. The missiles are fire-and-forget and integrate advanced infrared (and sometimes ultraviolet – IR and UV) seekers that can distinguish targets through their heat signatures.

MANPADS have many tactical and logistical benefits for users, especially when it comes to transportation, concealment, and ease-of-use, which means they have seen use in many conflicts since their inception several decades ago. For militant groups, MANPADS can be easily smuggled across borders and purchased on the black market for a cost that is relatively low, especially when compared to the devastating impact they could have.

MANPADS remain a relevant battlefield asset

While recent state-on-state conflicts have refocused attention on larger and longer-range SAM systems using radio frequency (RF) sensors and guidance systems, the use of MANPADS has far from disappeared. MANPADS proved critical for Ukrainian forces as part of a basic integrated air defence system, fending off low-level attacks from Russian fixed- and rotary-wing aircraft during the initial phases of the war and making it “prohibitively costly” to launch such sorties, according to the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI).

As the Ukraine conflict has shown, forces cannot simply have one layer of ground-based air defence (GBAD), and instead must have a multi-layered architecture that incorporates close-range MANPADS all the way up to long-range assets. The effectiveness of this has already been proven in these conflicts, and there is no doubt that adversary forces will look at this success to leverage the effectiveness of their own MANPADS in any future conflict.

As a result of this, MANPADS continue to be in high demand and state and non-state actors will look to buy and equip their forces with these capabilities for many years to come.

Previous conflicts have also demonstrated how smaller, less well-equipped forces can gain a disproportionate advantage over larger forces using MANPADS. Without appropriate or effective countermeasures, heat-seeking missiles can limit the use of helicopters and fixed-wing assets for critical battlefield missions such as resupply, medical evacuation, troop transportation and intelligence-gathering, which will have tactical and potentially strategic consequences for nations. Or, they will have to operate at very high risk of aircraft and aircrew loss.

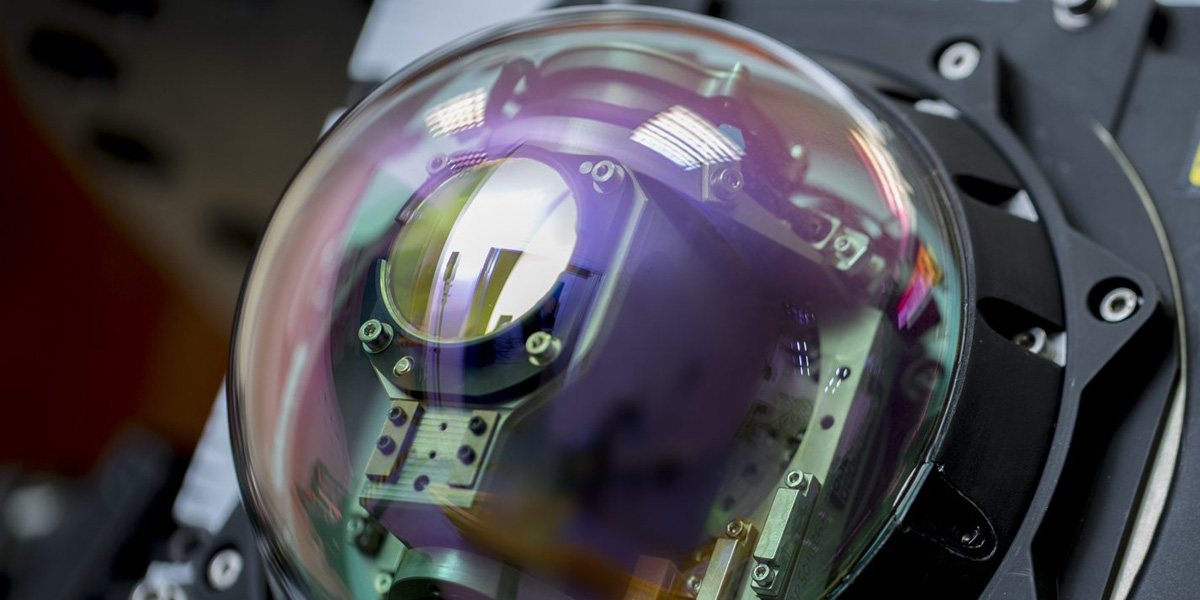

This was a constant concern for NATO forces and the counter-insurgency campaigns that defined the early 2000s, which led to Leonardo developing its laser-based Direct Infrared Countermeasure (DIRCM) system. Leonardo’s MIYSIS DIRCM uses multi-band high power laser energy to overwhelm a MANPADS seeker, and addresses the growing threat from increasingly sophisticated MANPADS that could distinguish between aircraft and traditional flare countermeasures.

Read more about what Miysis DIRCM is in our ‘DIRCM: Explained' article

Non-state actors and regional instability

The effectiveness of MANPADS militarily has not been lost on non-state actors such as terrorist and military groups.

Over the last few decades, a significant concern for many nations has been the proliferation of MANPADS to malicious non-state actors. Like the military domain, there are real-world examples of non-state actors effectively using MANPADS against aircraft, including civilian platforms. According to the US State Department, 40 civil aircraft have been hit by MANPADS since 1975, resulting in 28 crashes and over 800 deaths.

There have also been a number of near-misses, as well as thwarted terrorist plans that involved the use of MANPADS against civilian aviation.

“Despite an unprecedented global campaign to curtail the illicit proliferation of man-portable air defence systems, armed groups continue to acquire and use these weapons at an alarming rate,” said the Small Arms Survey, an independent research group based in Switzerland.

It is widely understood that the number of countries in which illicit MANPADS have appeared is now a global challenge, and includes advanced third- and fourth-generation systems. The majority of this MANPAD activity is occurring in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), with Europe coming second, and the distribution of advanced systems also concentrated in these two regions.

The proliferation of advanced systems in the MENA region, as well as ongoing instability and regional conflicts, will only present more danger to aircraft flying around the region, whether military or civilian. The latter could also include humanitarian aid flights organised by non-governmental organisations (NGOs), which have previously been targeted by MANPADS and would have catastrophic consequences not just for those on the aircraft, but also for those that require aid in a conflict zone.

Read more about how DIRCM keeps people safe

An increasingly complex and contested security environment

We are now in an era of a more contested and volatile world, according to the UK Ministry of Defence in its 2023 Integrated Review Refresh. The UK has identified four trends that will shape the international environment up to 2030, which are: shifts in the distribution of global power; inter-state, ‘systemic’ competition over the nature of the international order; rapid technological change; and worsening transnational challenges.

All four themes could have an impact on how the MANPAD threat evolves over the coming years, and how it impacts NATO and its allies. It is certainly the case that MANPAD technology is evolving at a rapid pace, and while legacy flares countermeasures may be enough to deal with older-generation heat-seeking missiles, they are simply no longer enough to counter the latest generation systems that are proliferating in MENA and elsewhere. The limited capacity is also a limitation that can only be resolved upon landing and re-arming, whereas MIYSIS DIRCM is effectively infinite in the number of ‘shots’ that it can fire, meaning protection for the whole duration of the mission.

The transnational challenge in particular will play a key role in the MANPAD threat, particularly as “large-scale migration, smuggling of people, narcotics and weapons, and illicit finance have become more acute”, according to the UK Prime Minister in his introduction to the integrated review. There are “multiplying effects” to several overlapping transnational issues that will compound global instability, which includes climate change and biodiversity loss.

These challenges could breed further regional instability, which would have a knock-on impact of the wider proliferation of weapons, including MANPADS.

This is a key reason why Leonardo’s MIYSIS is the world’s leading DIRCM system – both for military as well as civil aircraft – as it addresses the threat from advanced MANPADS that are now proliferating across the world, ensuring protection of people, platform and mission.

Read more about installation options for MIYSIS DIRCM

Conclusion

The threat from MANPADS has not disappeared, and as recent evidence has shown from independent organisations, the threat is continuing to evolve and grow, particularly in the MENA region. Whether it is a military or civil aircraft operating close to conflict zones or volatile regions, they will need a modern and operationally proven countermeasure system such as Leonardo’s MIYSIS to ensure that aircraft, passengers and crew return home safe.